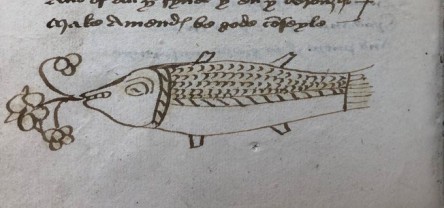

Some of the more entertaining and interesting manuscript mysteries surround the marginalia. For example, in Ashmole 61, a compilation of romances, exempla, saints’ lives, comic stories, and some prayers (mostly in verse), many texts are followed by the image of a fish, such as:

There is much debate over why a fish, what sort of fish is it, why the variations (and there are several), why do this more than once, what kind of person was the scribe (signed in a few places as “Rate” or similar) and so on. Animals figure pretty prominently in the margins of medieval books as part of the design and not, but that’s another discussion or several.

A quick search of the internet and you can find all kinds of marginal images and doodles from medieval books, from standard manicula (pointer fingers) like:

to abbreviations like “NB” for ‘nota bene’ (note well, or pay attention),

to my personal favorite:

on which a scribe has pointed to the smudge and told the reader it was not an error on his part, but rather a cat which had decided to pee on the book in progress, and a curse against said cat.

There are also plenty of medieval books that have explanatory notes and commentary with them, in fact with some books, their whole purpose was commentary, but the ones that don’t have that obvious context are in some ways more interesting, and often more entertaining to consider. We also have medieval books which seem to have been created by someone copying their favorite bits out of a range of texts. These commonplace books seem to have been pretty popular given how many of them survive from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and into the Early Modern era.

This brings me to contemporary books and how they might get used. I personally usually don’t write in the books I tend to read for fun, but I do write in textbooks and cookbooks.

As an undergrad I seem to have found it easier to take a few brief notes in my books, but mostly underline or arrow things of importance, such as passages pointed out by the professor (I also kept reasonably detailed notebooks with notes from lecture, but that’s another story). I now have found myself using those notes to write my own lectures and lesson plans, which in a few cases has meant transposing those notes and signal from one book (usually my original college textbook) to a new one (most often a later edition or similar but not identical title). Some of this might be the result of having to adjust to new versions of the same book, a situation unlikely for most of the Middle Ages given the general expense and labor involved in making a book copy. I also remember, only once or twice, with a used textbook, being able to make use of the previous owner’s notes. There are some documented marginal conversations and arguments in the margins of a few surviving manuscripts, but a significant amount looks more like what I’ve done to my own textbooks, although quite a few of the medieval scribes, scholars, and readers were a little more creative with doodles, not something I’ve done in textbooks. In some cases, these notes or doodles in the older books become a part of studying them for meaning, and you have to wonder what someone a few centuries from now might think of your student notes or textbooks (assuming you’ve altered them somehow as I have). In my own case, I have to thank past me for writing a little in those books, since it’s quite practically useful to me now, and I suspect it might have been a useful study aid at the time as well.

Again, on the practical side, in most of my cookbooks, there tends to be 2 types of notes: final verdict of recipe overall (ranging from J to “meh” to “nope”) and adjustments to the recipe I might have made, either in the ingredients or process. The final impression notes tend to be in the upper left of the recto page or upper right of the verso. There’s no real reason for it; that’s just how it seems to end up. On a more interpretive level, those phrases or images end up in that location because there’s open space in that part of the page in nearly all books of this kind. It’s also interesting to consider that nearly all of the notes are abbreviations or images of some kind, and how they might be taken when out of context. Would a smiley face be a positive or mockery? What does “ok” stand for or mean? Same for “meh” or “blech”, etc.? There might also be a question of ranking: is ‘nope’ better or worse than ‘bleh’?

In the ingredients, if there’s something I’ve left out, often a seasoning I either don’t have or know I don’t like (frequently basil, one of my least favorite herbs, or cumin, the spice I find most overused) it often gets labeled “opt.” (“optional”) or crossed out. If someone had my entire collection as it currently is, would they figure out that I don’t like basil much, or might they conclude that it was rare or otherwise inaccessible? Besides a reasonably sizeable collection of my own, I also have a few cookbooks owned by my great aunt and grandmother. These are considerably different in content, style, and look. These have virtually no marginal notes, but they do include a lot of inserts, things like magazine clippings or some notecards with recipes either written or glued on. Assuming future person noticed the difference in publication dates and had some understanding of the dating of the handwriting much in the way we now can do with a lot of medieval and Early Modern hands, how might they reconcile or not the two distinct types of books on those shelves? I usually don’t modify the general process except to sometimes note adjustments to times required, adjusting for my current equipment, or using the oven instead of the stove-top.

And then there’s the question of what about those recipes I either didn’t alter, forgot to annotate, or never tried for whatever reason? If there was not notation or spatter on the page, would the conclusion be it was never attempted or was followed exactly or made no particular impression? There are some studies of such things from the Middle Ages and later, but there’s no guarantee that similar impressions on the future/present would be reached even if the same kinds of study and interpretive techniques were applied.

It is an interesting thought experiment though; if someone who didn’t know me or my time and place found my book collections, what would they conclude about me if anything? You might also consider that fact that there are bookcases with books in them in three rooms in my home. What would that future person conclude about that? Would they notice that all the books in one case were all cookbooks (probably if they also had access to the room, which is the kitchen)? Would they figure out that one shelf of books in another room were those that had been read and set aside for clearing out later on (selling or loaning/giving away)? What would they make or figure out from the collection of mostly fantasy and science fiction with some random graphic novels tossed in? And what about that third shelf in a third room? Would they figure those were the books that weren’t in active or imminent use, and what would be made of all the other odds and ends on that set of shelves (a few mugs, some craft bits and bobs, a few odds and ends for the planter in the room, etc)?

It’s an interesting thought experiment, especially if you add in the more “academic” library of personal books I keep in my campus office. If the two collections were found 10 miles apart, would their mutual ownership be determined? And what would the variety, and there is plenty, on those shelves mean or add to the whole personal library picture? And that’s not even considering the handful of actual library books between the two locations…