Something interesting happened as a result of having to work from home until early August: a different type of course revision. Revising a course calendar and syllabus happens most terms, and what ended up happening isn’t even that new or interesting. The thing that was interesting is more that something most teachers known happened unintentionally since I didn’t have full access to all my textbooks, and how much of a difference it might make. Most every pedagogy bit of advice when it comes to general writing of assignments and choosing of readings has something to do with “choose the thing that adds progress towards the goals”, be it skill-based (like writing or reasoning) or content-based (like information).

Here’s what happened: I had to write the majority of my course calendars for a first-year composition course largely without access to the reader which I had left in my office, probably figuring I’d be back in there before I needed to worry about figuring out readings. This turned out to be about half true. On one hand, I was able to get most of the work done without the book, and I was back in my office almost 2 weeks before classes started, which is more than enough time to just add in reading assignments. On the other, while I was working out the actual calendar and assignment descriptions and break-ups into lessons, I had to do much of that work without ideas for readings to use for models and practice.

In the past, there have been times where I really wanted to use a reading but it turned out to not work out well in practice, and sometimes when a reading succeeded beyond what I had expected. The latter is the reason why Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” is again part of the argumentative reasoning section of the rhetorical analysis assignment. The former result though seems to have happened a few times per semester pretty consistently. However, this time around, it feels more like I was choosing readings based more on the skills students were expected to be working on because I’d already written out the composition specific elements of the assignments and lessons. Doing things this way, though not intended this past summer, seems to have removed the temptation to work in a reading that was more interesting than necessarily suitable to the skill to be considered. Like I said, this is a standard thing (matching reading and skills to course objectives) in theory, but it’s a lot harder to do than it sounds. We’ll have to wait and see how this semester goes to know for sure.

Prepping for the Fall 2020 semester has been extra ‘interesting’ because two of classes turned out to need what is apparently called “hy-flex” structuring and cohorting. Basically, the classes had to be split into two groups so they could alternate in-person and online. I have half of the class one day while the rest are online, then they switch the second day. “Hy-flex” is a set-up where both in-person and online options for a given class session are available, making it much easier if a student for some reason has to go online exclusively for a while. This situation has meant a lot more consideration of online pedagogy, which is something I’d been working on over the spring and summer, mostly through a webinar series hosted by my university system’s CETL and a few workshops for tools specific to my institution.

Here’s where things get a little more medieval, as opposed to the very modern current state of things and technology. Last spring I’d already decided to use Sir Gawain and the Green Knight as the literary test text for my theory-methods course. It’s old enough to have many applications done as both examples of theory and methods, and it’s complex enough to have a lot of possibilities for a range of interests. When we did general “Bibliography” day, I was genuinely impressed with the variety of what students found, when all they’d been asked to do was find one example of each of 4 standard types of bibliographical work. Although admittedly, that did mean I had less to demonstrate and explain than planned, but that’s one of the better reasons for some last minute lesson re-working.

I realized recently that for my other courses, first year composition and World Literature 1, that I was using an online annotation site a lot more than I have in the past. Part of this was by design as a way to get away from the standard discussion board, which degrades very quickly from actual discussion to posting stuff that address the assignment requirement (maybe), but not really interacting with either the other students or the content of the text under consideration. I got the idea from colleagues who have used such platforms before, and since I had to plan a lot more online work than past semesters, I figured it might be a good time to try. So far results are promising; there does seem to be some more interaction between students than on the standard discussion boards, and a little more detail in their references to the text. That last part makes sense in a practical way since they are literally commentating on a copy of the text, but it’s still nice to see them actually refer to specific textual details. I was a little worried about the difference in a few of the translations posted and those in the textbook, but that doesn’t seem to have been a problem thus far. It might make for interesting study to see which students used more: the book text with the accompanying notes etc., or the digital one.

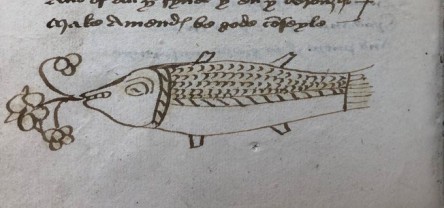

The other side, which is where the medieval comes in, is that I realized I’m essentially asking students to add their own marginalia to a shared text, almost in the way of a commonplace book or shared manuscript. The particular site I’m using does allow for some modern conveniences like up-voting, but it does preserve the record of who said what, where, and how responded, and how. Even though it’s only been about a week, and only one class has gone through this particular approach, it’s pretty clear that there is a little more interaction all around. There’s also an interesting range of voices evident, and I can’t help occasionally starting to drift into a fantasy analysis of how to interpret this person via their notes or what it might look like to someone unfamiliar with the actual person, even though I can easily look up who actually said that thing in that way, and I’ve seen actual faces/heard the voices/etc. to go along with the names. I also have to wonder if the marginalia idea is really more for me than the students. Framing this type of discussion as such might be novel for some, especially if they are the sort of student who like to take notes in their books, but not everyone does that. I’ll have to try it out and see how students respond.